2024-05-27-Use of Pointers

Strings

String Literals:

- data type:

const char *

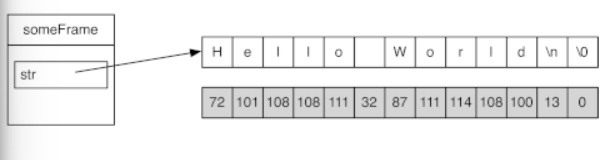

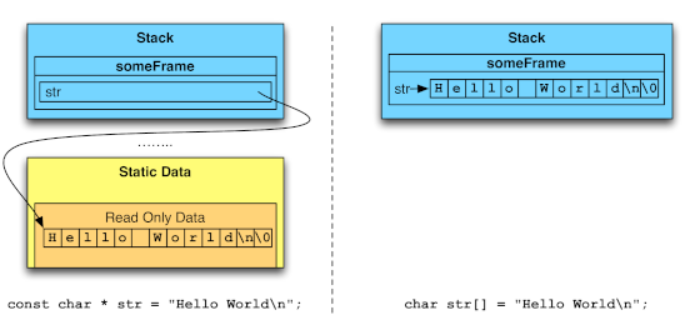

declare a string:const char * str = "Hello World\n";

str is a pointer, pointing to an array of characters, so the elements in the string will be stored in consecutive memory locations.

print a literal string:printf ("%s\n", str);

***Notice:

1 const: indicates that we can’t modify the characters pointerd to by str

2 Every string will be terminated with an implicit “\0” as nullcharacter - Result of modifying a string literal:

The program will carsh with segmentation fault -> indicating that access to invalid memory locations - Reason:

A string literal is stored into a read-only portion of the static data, and attempting to write to a read-only portion of memory will cause the hardware to trap in the operating systems. The hardware will move execution arrow outside of the program and put it in a particular function in OS and results in segmentation fault. - Load process:

The literal string is loaded into the memory by loader. Loader is a portion of OS that can read the executable files from the disk and initialize the memory appropriately. After the complier writes information to executable files and loader initialize the memory location, the loader will mark the read-only portion of the static data as non-writeable.

Mutable strings

- Method:

Array of characters

To create mutable strings, we have to create a variable that is stored in writable memory, such as the frame of a function call or dynamically allocated memory. - Example:

char str[] = "Hello world\n";

It is equal to:

char str[] = {'H', 'e', ..., '\n', '\0'}; - Difference between string declared as pointer to a literal and as an array:

-

Notice

The null terminator is counted in the array length, which can be explicitly presented in the second declaration above.

If we forget the null terminator, the program will carsh if we use the array for anything that expects an actual string. - Buffer overrun:

Buffer overrun is common error when the data we want to write is out of the declared array range, which will cover other values or impact the control flow.(LC3 buffer overrun example in sample)

String Equality and Copying:

- direct comparison and copy:

If we simply use == to judge whether the literal strings pointed by different pointers are equal, we are just judging whether these two pointers points to the same memory locations.

As for copying, we can simply change the arrow of a string pointer to point to the string we want. - “bitwise” compare and copy:

compare every character in the strings based(remember to judge null poerator)

For actual copy the same characters in the specified location, we can apply “strncpy( which we can specify the string size)” to achieve this. Notice the specified location may not have enough available memory addresses, so be careful.

strcpy prototype

char* strcpy (char* dest, const char* src);

It copies the string from src into the array at dest.

Multidimensional Arrays

Declaration, Indexing and Initialization

- Example:

double myMatrix[4][3]; - Declare:

Declare with multiple sets of square brackets, each indicating the size of corresponding dimension - Memory location:

The data in multidimensional arrays are also stored in consecutive memory locations, from the lowest dimension to highest dimension. - Indexing:

- Directly access the smallest element (eg.

myMatrix[2][1]), this expression can be a lvalue - If we don’t evaluate to the smallest element, the expression will be a pointer pointing to the array (eg.

myMatrix[2])

- Directly access the smallest element (eg.

- Initialization:

- Initialize the same way we initialize an array by simply adding layers.

-

Example:

1 2 3 4

double myMatrix[4][3] = { {1,2,3}, {7,8,9}, {2,4,8}, {5,6,7}}; - Notice: the first size in the multidimensional array can be elided, but the others can’t

-

Pointer arithmetic:

The multidimensional array pointer’s arithmetic based on the size of the array, which will take the highest dimension.

[[ Pointers#Aliasing and Arithmetic ]]

Array of Pointers:

- Represent multidimensional data with arrays that explicitly hold pointers to other arrays

-

Example:

1 2 3 4

double row0[3]; double row1[4]; double row2[2]; double * myMatrix[3] = {row0, row1, row2};

- Difference:

- Memory location:

In this case the memory location of each element don’t have to be consecutive, since the different pointers can point to different memory locations - Flexibility:

- The array don’t have to be the same size

- The pointer can be a lvalue, which means we can change where it points

- We can have two rows point at the exact same array

- Incompatibility:

This two ways are not compatible.

- Memory location:

Array of Strings

Declare strings as multidimensional character arrays:

- Example:

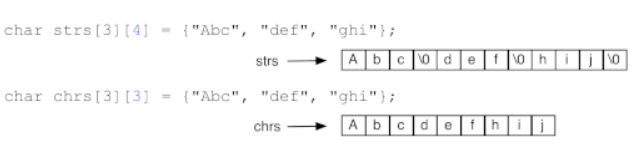

char str[3][4] = {"Abd","def",“ghi”};

char chrs[3][3] = {"Abc","def","ghi"}

Notice the difference between the two:

- Analysis:

The first statement can form a valid string with null terminator.

The second statement is correct iff we intend to use chrs only as multidimensional array of characters and not use its elements for anything which expects a null terminated string. - Limitation:

If we declare a multidimensional array of chars to hold strings of different lengths, then the size must be declared based on the longest one-> which will result in massive memory waste

Declare strings use array of pointers

- Idea:

We can solve the previous limitation and add flexibility by applying array of pointers - Example:

const char * words[] = {"A", "cat", "likes",NULL};

We can also add a NULL terminator to allow for one to write loops which iterate over the array without knowing a priori how many elements are in the array.

Function Pointer

- Idea:

Every instruction stored in the program are just numbers, and a function can indicate to a sequence of intsructions that perform a task. In this sense, we can regard the name of function as a pointer pointing to the address of the first code in that function. In sum, a function address can be seen as a function pointer.However, when we refer to a function pointer, we typically mean a variable or parameter that points at a function, but we can still absorb the idea above. -

Application:

Create a function pointer as a parameter to a function we are writing. We can apply this to eliminate the similar functions by creating a function table. We can also apply function pointer to call back functions.

Example:c void doToAll(int * data, int n, int (*f)(int)) { for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) { data[i] = f(data[i]); } } - Declare:

$ - Wrapper function:

Small functions that do little or no real computation, but provide a simpler interface - Passing a function pointer

[!Tip]

When defining a function pointer type, we should wrap the name with*and()like(*name), but when passing it to another function, we don’t need*If we don’t define a function pointer type and directly pass a function pointer, we should add

*when employing it.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

//Define a function pointer

void (*Func_ptr) (int);

//Or we can define by typedef, it is equivalent

typedef void (*Func_ptr) (int);

//Define a function that matches the function pointer

void print_Func (int value){

printf("%d", value);

}

//Define a function that takes a function pointer

void exe_func (Func_ptr pass_func, int arg){

pass_func(arg);

}

int main(){

exe_func (print_Func, 42);

return;

}

Sorting elements Example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

//Now we implement a sort operation on a general kind of data

//Specify the is_smaller function before

//Input: base: pointers to the array, n_elts: number of array elements, size: number of bytes per thing, function pointer

//Return value: 1 on success, 0 on failure

int32_t isort(void* base, int32_t n_elts, size_t size, int32_t (*is_smaller) (void* t1, void* t2))

{

//declare some local variables

char* array = base;

void* current;

int32_t sorted; //indicate the sorted element

int32_t index; //indicate the comparison index

//Different kinds of data have different size -> dynamically allocate the size

if (NULL == (current = malloc(size))){

return 0;

}

for(sorted = 2; sorted <= n_elts; sorted++){

//copy the current thing for comparison

memcpy(current, array + (sorted-1)*size, size)

//inner loop for comparison

for(index = sorted-1; 0 < index; index--){

if ((*is_smaller)(current, array + (index-1)*size)){

//move the comparison object to the right

memcpy(array + index*size, array + (index-1)*size, size);

}else{

break;

}

}

//find the right place

memcpy(array + index*size, current, size);

}

free (current);

return 1;

}

Lists

Summary of pros and cons of dynamic resizing

- Pros:

easy to implement

array uses contiguous memory - Cons:

copying cost

waste space

LIsts Basic:

- Motivation:

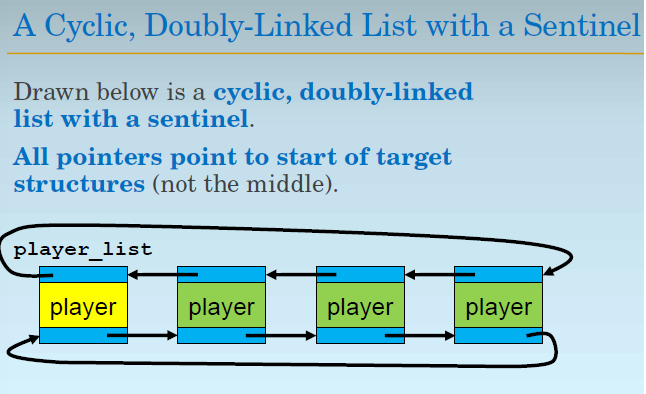

Sometimes we just need to resize some elements in the whole data structure, but previous dynamic resizing wastes much space and produces copy cost. So we come up with a more flexible data structure which eliminates the hassle of dynamically inserting and deleting node for changeable data and achieves some abstract data structure. - Structure:

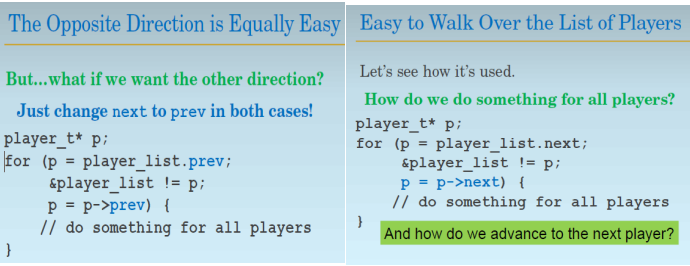

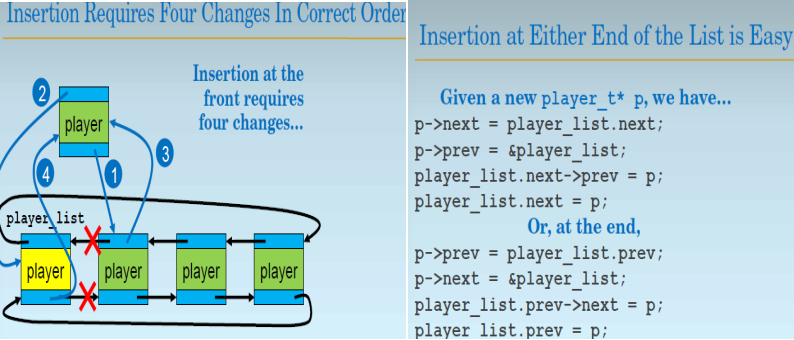

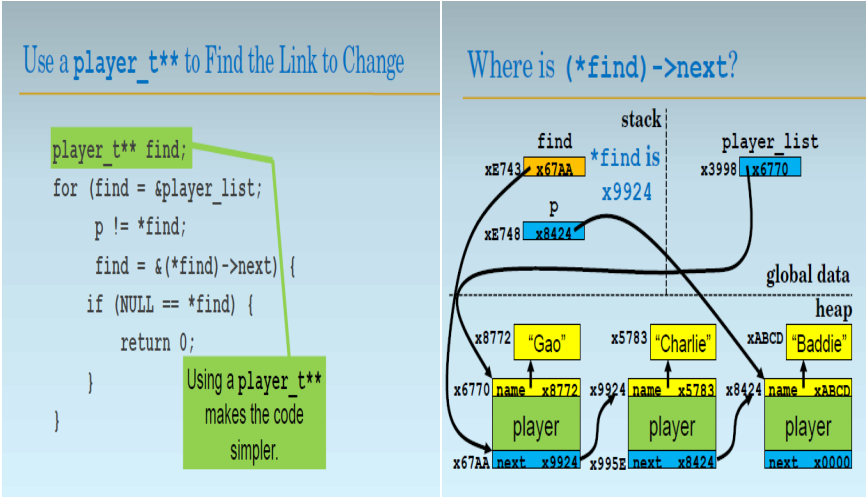

Every element of lists is stored in a node, each node consists of a data element and a pointer to the next node. Based on the different arrow structure, we can categorize lists into several kinds… - Basic operations:

- Inserting node:

Insert at the beginning-> just change two elements

Note the order matters! First point the arrow of new_node to the next node, then point the beginning to the new node

Sometimes remember to use NULL to examine whether memory allocation has succeeded. - Deleting node:

We must walk through the whole list to find the target node then change the pointer.

Note: we must be cautious about free order from low levels to high levels

*find = p->next

free (p->name);free (p);`

- Inserting node:

More operations and complicated structures

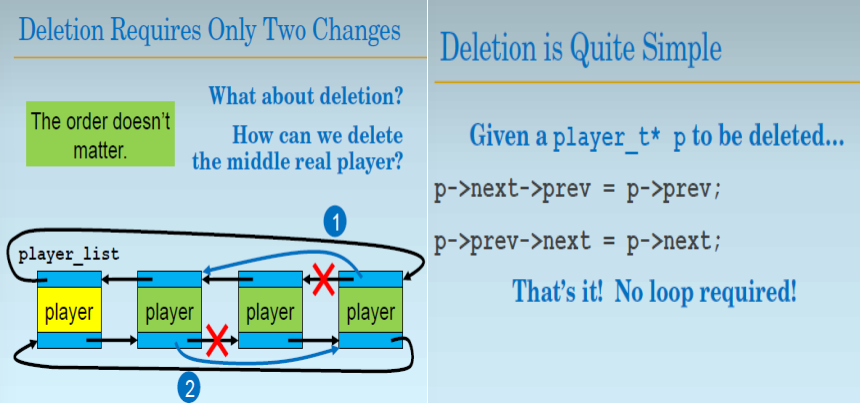

Use a Sentinel and a Cycle List to simplify the code

- Operations:

- Deleting only requires two changes:

- Sentinel links to itself when the list is empty

Sentinel is a special node which can serve as a fixed node and can make the head and tail of the list easily be identified. It can simply the list operations - Pointer usage:

Organize groups of structures in different ways: orderings, relationships properties. - Example:Abstract Syntax Tree(ASTs)

- Node: Represent operators or statements

- Relationship: Represented as pointers to other nodes

Operands: relation to operators

Operations:relations to statements